I just started reading one of the books I received for Christmas, titled, Chasing the Sun: The Epic Story of the Star That Gives Us Life, by Richard Cohen (Random House, 2010). As might be expected, early on Cohen deals with the various ancient beliefs about the sun and the solar cycles, and in particular the two annual solstices.

Two sentences grabbed my attention: “On the year’s longest day, it [the Sun] rises closest to that hemisphere’s pole. On both occasions it seems to stop in its path before beginning to double back” (p. 15). Stop in its path? A couple of sentences later, Cohen states, “…for two or three days, the Sun seems to linger for several minutes–hence the word ‘solstice,’ from sol (sun) and stitium (from sistere, to stand still: ‘armistice’ translates as ‘weapon standstill’) (p. 15).”

If you do what I do when I suddenly make a connection between a seemingly everyday event and a biblical miracle/event, I grabbed my Bible and looked up Joshua 10, the narrative where Moses’ successor, Joshua, petitions the Lord to make the Sun and the Moon stop high overhead so he can have the daylight he needs to complete defeating the Amorite Coalition led by Jerusalem King Adoni-zedek who have had the Gibeonites (an ally of the Israelites) under siege.

Adoni-zedek is important for another reason. At least six letters he almost certainly wrote are part of the Amarna Letters dated circa 1388 BCE-1333 BCE, dispatches he sent to the Egyptian Pharoah complaining about “raids by the Habiru.” If this reference is an authentic reference to the Hebrews’ invasion of Canaan, the historicity of Joshua 10 is significantly enhanced, regardless of the other details the biblical author wrote into his account.

There are two other relevant issues in this account the writer of Joshua chose to include as something the reader should know about the battle. First, though, a bit of geography to set the scene.

The geographical distances involved in this narrative are quite small by modern standards. The ancient site of Gibeon has been well established, located on one edge of the current Palestinian town of Jib. It sits less than 20 miles NE from Jerusalem, but it is over on the north side of the mountain ridge that separates Jerusalem from the Kidron Valley. Keep that in mind.

Gilgal is a bigger problem. Its exact location is still up for debate, but the consensus site at this time places it about a mile NE of Jericho deep in the Dead Sea Valley. In one respect, if the text is historically reliable and Joshua took and then destroyed Jericho it is plausible that he might have settled the Israelites there temporarily, but stategically it is a less than ideal site and creates another problem as I’ll describe below.

Returning to the text: First, to move his army from Gilgal deep in the Dead Sea Valley, all the way up and over the southern slopes of Mt. Ephraim to Gibeon, whom Joshua was bound by treaty to defend (9:14), he had to quick march his troops overnight to the city. Jericho is 846 feet below sea level, so the entire army had to first climb to sea level and then over the Central Mountains, a total increase in elevation of about 3500 feet! However there appears to have been a well established trade route from Jericho to Michmash near the summit, after which it was downhill, for the most part, to Gibeon. Clearly these were the Israelites’ “special forces,” for as the text says, they were “the best fighting men” (10:7). This specially trained unit alone could have made such a physically grueling march. Regardless, Joshua’s tactic was effective despite whatever fatigue his army was feeling. They arrived early in the morning at the encampment outside of Gibeon. This time of day undoubtedly was the least expected moment the Jerusalem-led forces would have anticipated an army to appear out of gloom of dawn. The Israelites were in full battle array. The other guys were most likely sitting around their campfires eating breakfast.

Second, the Amorite soldiers, quickly sizing up the situation, knew their only chance to survive was to beat a hasty retreat, having no time to put on their armor. And to their great misfortune, in their rush to escape the ranks of the Israelites already engaged in battle at the far edge of camp, they ran right into a massive hail storm. The text attributes the storm to God. But as is not that uncommon in Tornado Alley here in the U.S., hail measuring the size of golf balls all the way up to grapefruit is not impossible nor that uncommon when the conditions are right. Caught out in the middle of this meteorological bombardment, being driven by Joshua’s troops bearing down on them from the rear, the writer, clearly speaking from experience, makes a very matter-of-fact statement: “…and more of them died from the hailstones than were killed by the swords of the Israelites” (10:11). A careful look at a topographic map of ancient Israel shows Gibeon sits on the north slope of one spur of the Ephraim Mountain range and is exposed to any tropical moisture that would come spiraling out of the NW Mediterranean Sea. Thunderstorms with significant hail probably were not that uncommon. Particularly if given a little nudge by God.

Joshua, however, is not a “leave half the job unfinished” kind of commander. God had promised all the Amorites would be delivered to Joshua’s army so they could kill every one of them (See: herem), and he was going to make that happen.

Joshua in the midst of the battle asks the Lord to stop the Sun and the Moon over different valleys, that are identified, interestingly enough. Since we know where Gibeon was located, the Sun would be high directly over the city. We also know the location of the Valley of Aijalon where the Moon was commanded to stop. The problem is that Aijalon is just over the hill from Gibeon, a small valley that opens out onto the broad Plain of Shephela. In terms of line of sight, that would seem to have the Sun and the Moon right next to each other, with the Moon being slightly to the observer’s right. And that’s a problem that will be discussed below. This Sun/Moon configuration may just have to be left as a supernatural act by the God. On the other hand, we have at our disposal some powerful tools to examine a hypothesis of what might have happened.

Part 2

We considered above the possibility the Battle of Gibeon perhaps had an astronomical component to it that could be identified by looking at the history of solar eclipses in that region. We have also examined the route that Joshua and his army of select warriors had to take to get from Gilgal, located adjacent to Jericho deep in the valley of the Dead Sea at a below sea level elevation of 846 feet (one of the deepest land canyons on the globe), over the Central Mountains of the Mt Ephraim Range, a vertical rise of 3500 feet and then down to Gibeon, which sat less than 20 miles north-east over the hill from Jerusalem.

According to the text, this forced quick-march was accomplished in a single night. The distances, however, teeter on the edge of credulity. According to Google Maps, the walking distance from Jericho to the modern town of Jib, the known site of Gibeon, is 61.5 km (38.3 miles) assuming the army roughly followed the known trade routes fanning out from Jericho at the time and would take approximately between 13 and 14 hours.

This modern route however assumes walking on the sides of well developed motorways, and not an expeditionary force of soldiers in full battle armor, in the Bronze Age, in the dark to avoid detection, and very possibly avoiding the trade route between Jericho and the town of Michmash (modern Mukhmas) at the summit. Nevertheless, if the author assumed that the army left early enough the previous day so the march only took one night, then it is possible.

Another issue is the dating of the Book of Joshua itself. Although many scholars today date the work sometime during the era of the Babylonian Exile, circa 7th Century BCE, the core events may be attributable to the Second Millennium BCE. If the Egyptian Mernepthah stele is dated accurately circa 1209 BCE, and is, in fact, also an authentic historical mention of the Hebrews then the assertion can be made that that the conquest of ancient Canaan perhaps took place sometime between 1500 and 1300 BCE as Gerhard von Rad suggested.

Taking those assumptions, I entered the dates and set Jerusalem as the primary viewing site into my astronomy software (TheSky6 Serious Astronomer Edition by Software Bisque) and launched the Eclipse Finder. In ten year increments I was able to examine the date, time and track of every eclipse reasonably visible to an observer in Jerusalem for those two hundred years. I excluded those eclipses that just grazed a tiny percentage of the sun or were so close to sunrise that they were likely to go unnoticed and therefore did not fit the description of a major midday event that could have been to Joshua’s advantage. I included total, annular and partial eclipses.

The Eclipse Finder generated 30 events for that two century period. It is, of course, impossible to know which of those events were observed, or what the weather conditions made possible viewing any particular eclipse. Additionally, as any student of the Bible can tell you, the ancient Hebrews were not great observers of the sky, or at least they didn’t appear interested in communicating astronomical events in much detail in the text of their (and our) scriptures. There is an interesting irony to this apparent reality. The ancient cultures of Mesopotamia and Egypt both were doing sophisticated astronomical observations in this period of time (White, 2008, Babylonian Star Lore London: Solaria). I’ll come back to that below.

First, some modern geography. Jerusalem sits at 31°47”N; 35°13” E. For comparison, the 32nd parallel enters the United States at El Paso, TX, located on the far western tip of the state and creates the state line between Texas and New Mexico. Continuing east, it bisects the rest of Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and reaches the Atlantic Ocean right at the southern-most tip of South Carolina. On the opposite side of the Atlantic it makes landfall in Morocco, crosses the Central Sahara Desert through Algeria and Tunisia, and then enters the Mediterranean Sea just slightly south of Tripoli, Libya. Clipping the northern peninsula of Libya, it is then drawn across the southeast Mediterranean Sea just north of Egypt, until it connects with Israel and Jerusalem.

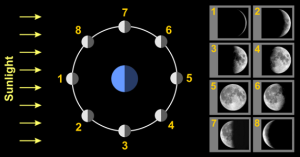

At this latitude, Jerusalem sits only about 9° north of the Tropic of Cancer, which is the northernmost latitude (23°N) that the Sun will appear directly overhead at the Summer Solstice (approx. June 21st). Because the city is located close to the Equator, the Earth’s axial tilt (also 23°) and the Moon’s orbit (on what is called the ecliptic) will naturally generate more visible eclipses than can be observed from more northern locations. Thirty eclipses, therefore, over a two hundred year period are a natural consequence of the concurrent synchronicity of the Earth’s daily rotation and orbit around the Sun, as well as the Moon’s orbit around the Earth. Nevertheless, only just over a third of these events were total eclipses (13 of the 30).

My Big Guess

I have to be honest with the text as presented. It does not mention an eclipse, and as I have said before the author ascribes God’s direct influence on both the Sun and Moon rendering them stationary and soon after causing the catastrophic hail storm. But as we have learned from the research regarding the Star of Bethlehem, it is reasonable to explore what natural events might have influenced the author, or those who were present at the event, to interpret these two phenomenon as clearly and literally an act of God.

The historicity of the narrative in Joshua is enhanced if astronomically-validated events can be identified at the time this battle is to have taken place. It would also mean that, assuming the date of the Book of Joshua is somewhere in the time span between 700-500 BCE, the author(s) had access to extant historical material from which this account was written. If it was during the Babylonian exile, and knowing the Mesopotamians’ extensive study and writings about the sky (North, J, 2008, Cosmos: An illustrated history of astronomy and cosmology), it can be conjectured that the Israelite scholars, might possibly have had a calendar or sky description source from which they based their narrative. Therefore, I am going to hypothesize that they did.

The thirty eclipses between 1500 and 1300 BCE can quickly be narrowed down to a handful if we follow two assumptions.

First, as Cohen in Chasing the Sun pointed out in Part One, the Sun particularly at the time of the summer solstice seems to linger at its highest point in the sky for a few days on either side of the longest day of the year in the Northern Hemisphere. The text also implies the Sun was high overhead. If the battle took place during the vernal or autumnal equinoxes, the angle of the Sun in elevation from an observer on Earth would not meet the physical description of the Sun’s location that day. So we can look for eclipses that occurred in that general time frame of the solstice over that two hundred year period.

The second assumption is that perhaps the eclipse began at sunrise, or was in totality at sunrise, giving the day the appearance of starting very late, and by the time the eclipse was over, the Sun would have seemed to have appeared not at dawn but close to noon. This might be interpreted as the Sun having stopped in the sky, and near the longest day of the year, it naturally would provide a longer period of daylight.

A dawn extended by an eclipse would also potentially lend authenticity to the claim regarding making the march from Gilgal to Gibeon in one night. If the sun was totally blacked out by the moon at the time of sunrise, Joshua and his forces would have been given a rare gift to approach the Amorite camp under the cover of darkness and dusk, allowing for the possibility of a surprise attack, as I said before, right when the Amorites were eating breakfast. Caught unawares, likely not having donned their armor, they were at their most vulnerable, especially as the Israelite forces seemingly came out of nowhere and began to cut them down. Under the mandate of cherem, if God had commanded them to kill every person and beast in the camp, they were obligated to do just that.

Here, then, are the best candidates for producing the right kind of eclipse at the right time of the year that may have been the underlying natural event of a very divinely guided military campaign in Joshua, chapter 10:

| Date | Type | Begin³ | Maximum | End |

| June 23, -1442 | Total¹ | 4:27 | 5:26 | 8:07 |

| June 24, -1396 | Annular | 4:48 | 7:38 | 11:08 |

| June 3, -1348 | Total² | xx:xx | 4:43 | 6:53 |

| June 5, -1302 | Total | 7:34 | 10:34 | 13:54 |

Note 1: Eclipse was 95% full at sunrise.

Note 2: Eclipse was at totality at sunrise.

Note 3: All times Jerusalem Local in 24-hour format.

These four eclipses come closest to meeting the assumptions described above, from the description in the biblical text, the scholarly hypotheses regarding Joshua’s lifespan, and the estimated centuries in which the Israelites could have been moving into Canaan and conquering the cities and peoples who were already there.

But which eclipse is the best choice? Not knowing the date except in the scope of the broadest historical theories is a major hindrance. Each event has its pros and cons.

- The 1442 BCE eclipse took place on June 23, which is very close to the summer solstice, was 95% full at sunrise, so it would have extended the perception of darkness, or at least a very deep dusk, giving Joshua’s forces an unexpected cover of darkness as they approached the Amorite camp. Its drawback it that it was not a very long event, reaching totality at 05:25, after which the light would begin to increase and it would have been fully sunny just after 8:00 a.m.

- The 1396 BCE eclipse was annular. In this type, the moon covers only part of the sun, which at totality produces a bright ring of sunlight around the circumference of the disk. For Joshua, the darkness would not have been as deep, although it creates duskiness that some find odd, even to the point of feeling a bit spooky. An eclipse of this sort, although strikingly beautiful to our modern eye, might have been very disconcerting to the Amorite forces. Joshua’s warriors, too, may have been unsettled by the eclipse’s unusual visual characteristic, but keep in mind they were on a mission to save an ally and they firmly believed God was on their side. Whatever the event was, the Author was convinced this was an act of the LORD, and so it is possible to theorize they were able to put aside their discomfort and continue the march toward Gibeon. This eclipse has the advantage of taking place on June 24, again very close to the longest day of the year, as well as its duration of around six hours, returning to full sunlight an hour before noon. Put together the attributes of this eclipse make it a viable candidate for the Joshua narrative.

- The 1348 BCE eclipse rose in totality at about a quarter to 5 a.m. The sun was fully visible at 6:21, making it a very short event, and in my assessment a less viable candidate than the one in 1442 BCE. Also, it occurred on June 3, well over two weeks before the Summer Solstice. Its one advantage might have been a very dark sunrise allowing Joshua and his men to get much closer to the Amorites before they launched their attack on the camp.

- The last eclipse in 1302 BCE was also in early June but unlike the 1348 event, it began at 7:38, plunging a seemingly normal late spring morning into a spectacular and dark solar event, creating a total eclipse that lasted from start to finish six and a half hours. The end of the eclipse at nearly 2:00 p.m., is important to note because at 12:00, a significant percentage of the sun would already be visible, and it is possible to speculate that the perception of the sun and moon together at high noon, with the moon slowly pulling away from it could have looked like both of the heavenly bodies were standing still.

- The Moon problem. The narrative is explicit that the Moon stopped to the right of the Sun high over the valley of Aijalon (10:12), which is southwest and on the south side of the hill from Gibeon. This creates a problem. The astronomy simulations in all cases clearly show that the Sun, not the Moon, moves to the right and that since the Moon is so much closer to the Earth, it is not visible in the daylight. The physics of this is straightforward. The Sun appears to move because the Earth is rotating on its axis. The Moon actually moves because it is in orbit around the Earth. The result is the Sun visually moves to the west faster than the moon.

In the end, my preferred choices are the eclipses in 1396 BCE and 1302 BCE. Both seem to have attributes that would provide Joshua’s army with a strategic advantage as they approached the Amorite’s camp. I acknowledge that I can’t prove that either one of these events answer the question about the Sun and the Moon standing still asserted in 10:12-13. What is not in doubt is that the author believed the events in the sky, both the astronomical and the meteorological were a direct result of the LORD fighting on behalf the Israelites:

There was no day like that before it or after it, when the LORD listened to the voice of a man; for the LORD fought for Israel (v. 14, NASB).

Several final questions remain: Did Joshua know in advance what was going to happen? We know from the history of astronomy that predicting eclipses was one of the major efforts of the astronomer/astrologers of the ancient Near East. As I mentioned above, did the author of Joshua have access to Babylonian astronomical texts to guide him? Did the author have access to manuscripts saved when Jerusalem was sacked and the Israelites taken to Babylon? I again can only speculate, but the combination of these two possibilities raise interesting questions for further research on this fascinating narrative.

The alternative that I find very dissatisfying at best, although it cannot be ruled out, is that Joshua (and the Pentateuch) were written solely based on oral tradition or were essentially works of sacramental fiction. Granted, for a people in exile, far from their beloved homeland, knowing from stories by the elders that their holiest city, Jerusalem, was left in ruins, these books, even if largely constructed as mythology, because of their elegance and genius as narratives of faith, would have been read with great reverence. As such it is understandable how in a matter of a few generations they might be regarded as historical accounts, even if the foundation came from an oral tradition of uncertain veracity.

I prefer the hypothesis that if the actual date of the authorship falls within the time of the Babylonian Exile (7th Century BCE), that the Israelite scholars were introduced to the treasure trove of information in the libraries that have been found in Babylon (and many other Mesopotamian cities). North (2008, Ibid.) makes two relevant points. First, he describes the high level of astronomy being done during the Hammurabi Dynasty, ca. 1800 BCE- 1500 BCE, with the quest for predicting eclipses being exceedingly important, and second, the resurgence of Babylonian astronomy in the so-called “period of independence” from 612 BCE-539 BCE. The proximity in the first case to the dating of Joshua and the Israelite conquest of Canaan, and a thousand years later the Babylonian Exile simply cannot be ignored as creating the potential for reliable astronomical information Joshua as well as his chronicler may have had.